In my work as the Elementary Visual Art Specialist for the Juneau School District I have for years puzzled about art being an avenue for complex thinking for students. For the last six years, I’ve been very involved with a grant-funded PD project in the Juneau School District called Artful Teaching. We have a large cohort of teachers learning together through workshops and small collegiate study groups called “Art Labs.” We are exploring arts integration and culturally responsive teaching. One of the areas of learning for us has been through Project Zero Harvard and their Visible Thinking routines and practices. I’m experimenting all the time now with how to deepen thinking through art. The following shares a project around students’ school environments.

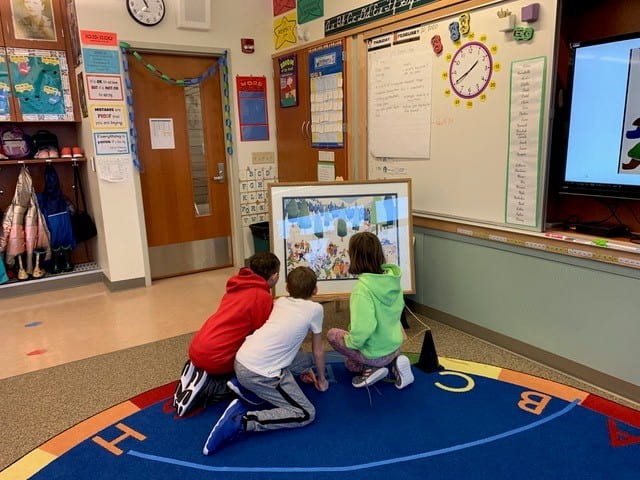

Kids walk by the art installed in their schools every day without noticing it. My goal was to use the practices of “slow looking” and thinking routines to help students pause and really notice, learn about and appreciate the art that surrounds them in their school home. These were my big questions:

- How can we facilitate students “Slow Looking” at art (or anything?)

- What are specific thinking routines that work well for extended looking and learning?

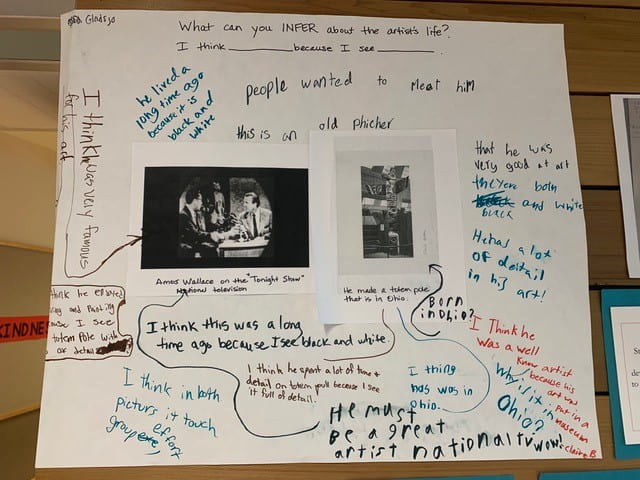

- Can we see evidence of complex thinking by making thinking visible?

So much of the art that surrounds us in our school and community is Northwest Coast art, particularly the house screens and panels that have been provided to our schools. It was important that neither I nor students make any presumptions about this artwork which is so rich in intended meaning and tradition. I connected with the building cultural specialists for consultation, and in several cases, very involved co-teaching. Three steps emerged as a reliable path:

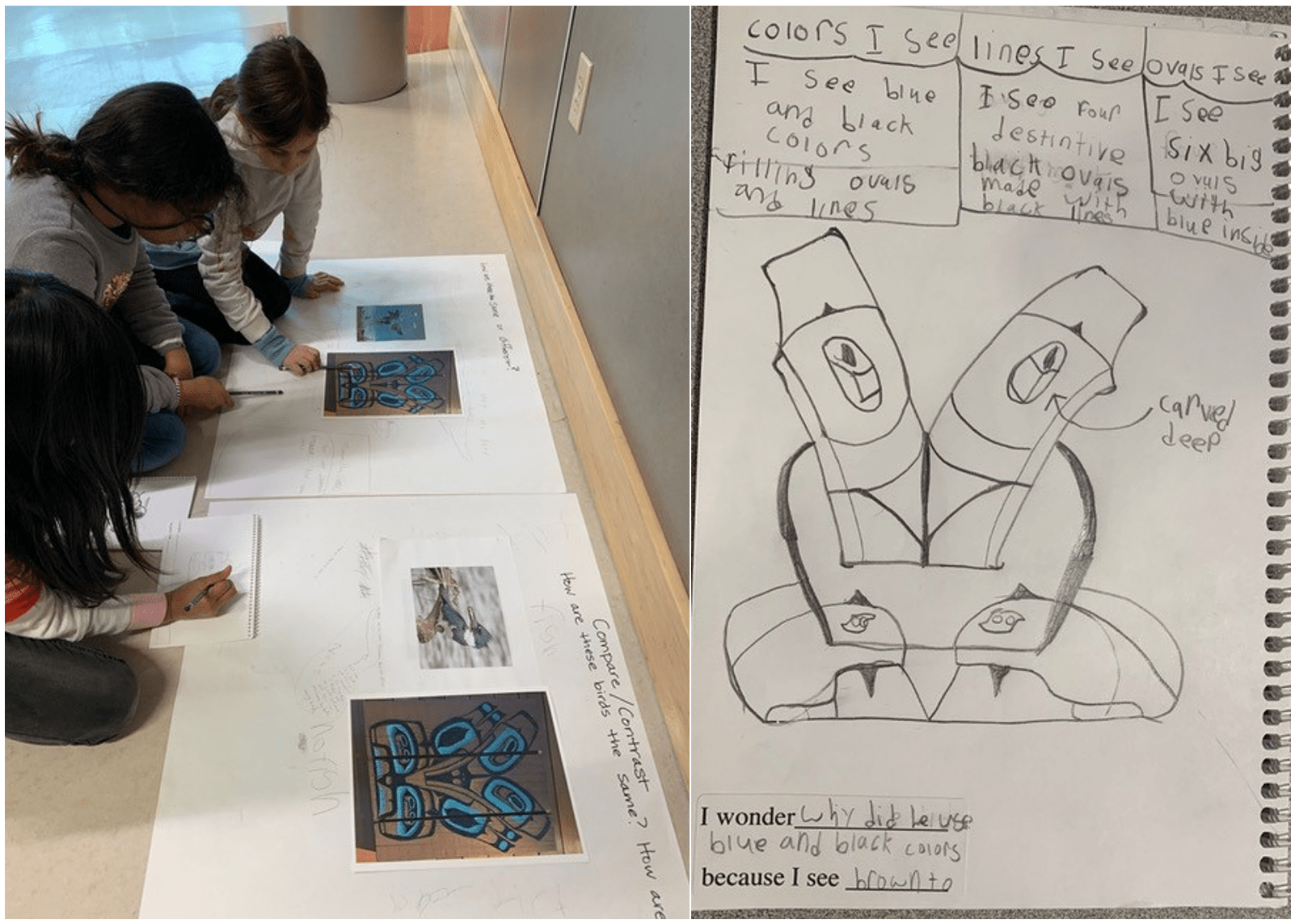

- Start with a guided “slow look” that focuses on the formline, shapes and colors. This was an almost meditative time of quiet, guided by small prompts.

- Give time for students to sketch the art in their sketchbooks. Drawing invites and requires one to slow down and examine lines, shapes, patterns, images, and makes us curious about meaning.

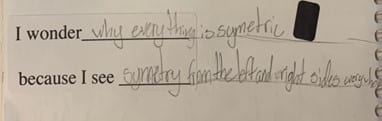

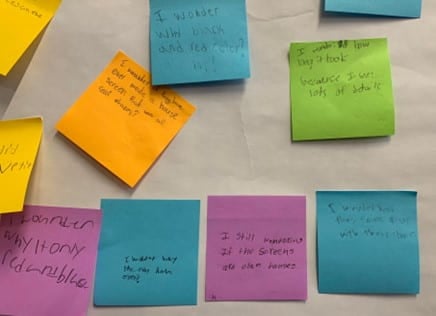

- Use a sentence stem to support respectful wondering. I didn’t want students to make inferences about the formline designs without any knowledge about the history or intention of the art, but I did want them to engage and be curious. Sentence stems we used were: “I wonder…because I see….” Another stem we used was: “When I see…it makes me think…” Giving them a sticker with this question stem helped

4. Provide opportunities for supported cultural learning about the art.

5. Revise our questions and future learning based on new knowledge. Students returned to their initial questions: Has your question been answered? How would you revise it? What are questions we still have?

Samples of student work (drawings and writing) gave us opportunities to see the student thinking. What was the level of complexity? Were there misunderstandings that need clarification? Did they have some authentic questions that gave evidence of real curiosity? What could be next steps for research and learning about the topic? My goal was to leave the teachers, students and cultural specialists with a path forward for more learning.

These practices for “Making Thinking Visible” have helped me connect to the root of what I feel is important about our schools–that they be places we give opportunity for students to think, share their personal perspectives, and listen to others.